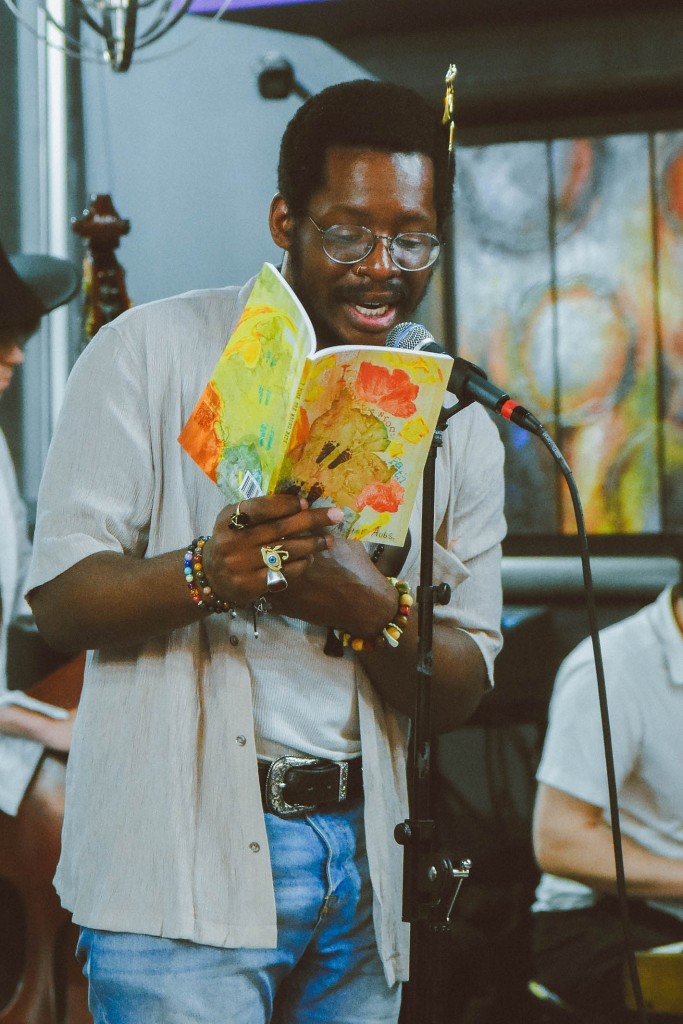

From rural midwest poetry to a French residency, how Aubrey Barnes continues to share his uncompromising voice

Barnes, who has previously performed at the Watershed Voice Artist Showcase in Three Rivers and had several works published by the news and culture magazine, was recently awarded a writing residency at Chateau Orquevaux in the Champagne-Ardenne region of France. He described the experience as life-changing.

“The artists — writers, painters and other creatives — would gather. We walked together, explored the grounds, shared our art, cried, laughed and built deep bonds quickly. It was transformative.”

Aubrey Barnes, nationally known as “Mister Aubs.,” describes himself first not as a performer, but as a thinker.

“As an artist, I would describe myself as a thinker — someone who observes the world both outwardly and inwardly and does my best to articulate that world,” Barnes said. “I first try to make sense of it for myself, or challenge myself through it, and then offer it to my audience.”

Barnes, who is based in Rock Island, Illinois, has spent more than 23 years cultivating that relationship with writing. What began as something shared privately with close friends and family has grown into a career spanning performance, mentorship, youth programming and, most recently, an international writing residency in France.

A poet shaped by rap

Barnes often says his introduction to poetry was unconventional.

“I had a ‘fish out of water’ experience when it came to being introduced to poetry,” he said. “I wasn’t initially inspired by Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson or Langston Hughes — though they’ve offered powerful narratives to the world.”

Instead, poetry entered his life through rap.

“As an 11-year-old Black kid growing up in the Midwest in a space where art wasn’t prioritized for youth exposure, my introduction came through rap and battle rap,” Barnes said. “I would go home and watch ‘106 & Park,’ ‘The Basement,’ and SMACK DVDs. I didn’t think I had the talent to rap, but I knew I had stories to tell. That was enough inspiration to begin writing.”

He started by documenting daily life. As he grew older, the writing deepened — into love, vulnerability, politics and social reflection.

“My voice still carries the aesthetic echoes of rap and battle rap,” he said. “I’m honoring both my inward and outward ponderings as a human having a human experience.”

Creating space where it didn’t exist

Pursuing poetry professionally in the Midwest, Barnes said, came with obstacles — especially as a Black artist.

“Growing up, much of my art was shared privately,” he said. “When I began taking it seriously in my early twenties, I started noticing the hardships of making art professionally here.”

Some of those hardships were direct.

“I’ve been asked to leave open mics because people weren’t familiar with poetry as an art form. I’ve heard side comments at bars and coffee shops where I was invited to feature. There was even a time in LeClaire, Iowa, when we were performing poetry at a farmers market and the mayor told us to stop.”

Those experiences revealed how difficult it can be to sustain creative work in communities that it is foreign to.

“Those experiences show how difficult it can be to practice poetry as a profession when people don’t yet understand or value the art enough to provide space for it,” Barnes said. “I’m grateful to say that now we host an open mic that has been running for almost 13 years.”

That open mic, he said, exists because of those earlier struggles.

Mentorship helped shape that transition. A former mentor encouraged him to lead. Fellow poet Chris Britton — whom Barnes calls his “brother in poetry” — pushed him creatively and influenced how he works with youth.

Barnes has also received mentorship and recognition from spoken-word poets including Black Chakra and Dr. Haki Madhubuti. For a writer from Rock Island, he said, that affirmation was transformative.

“As someone from a small Midwestern town, to be recognized by poets of that stature expanded how I practice and teach spoken word poetry.”

Writing from complexity

Barnes describes his upbringing as layered rather than linear.

“My upbringing was nuanced,” he said. “I lived in a mid-to-upper-class neighborhood near a college — a place that felt safe — yet close enough to the hood that caution was always present.”

His friends spanned racial and socioeconomic lines.

“My neighbors and best friends were Mexican. I was in Boy Scouts with predominantly white kids. I ran cross country and track with people from various backgrounds. I also had friends who were gang-affiliated or involved in violence.”

Because of that range, he resists binary thinking.

“I don’t write from a single-sided lens,” Barnes said. “I don’t feel confined to rigid binaries. Growing up in a community like mine allowed me to see complexity — to ask more questions than point fingers.”

That perspective shapes how he approaches race and division in America.

“When it comes to color politics, I often say that the divisions are constructed — shaped by prejudice, conditioning, inherited trauma and reactions to pain,” he said. “These divisions are illusions, but very real in their impact.”

Even while acknowledging that impact, Barnes returns to something deeper.

“I am human before anything else,” he said. “Even beyond human, I am spirit and energy — identities that don’t have a color or genealogy. My writing wrestles with that paradox — the very real illusions we live within.”

When asked what responsibility he feels as a Black artist in this moment, Barnes’ answer is firm.

“My responsibility is honesty. Complete honesty.”

He paused, then continued.

“The world has the capacity to make us dishonest — and I’ve been dishonest in my life at times, in ways that caused harm. So now I strive to be truthful in how I speak about political realities, social issues, violence, misinformation — all of it.”

After that, he says, the outcome is no longer his to control.

“My job isn’t to convince anyone,” Barnes said. “My job is to be honest.”

A season in France

Earlier this year, Barnes was awarded a writing residency at Chateau Orquevaux in the Champagne-Ardenne region of France.

“It honestly felt serendipitous,” he said. “I kept seeing the residency on Instagram repeatedly until I decided to apply.”

He applied without expectation.

“A large part of writing is submitting without attachment to the outcome.”

Two weeks later, he received acceptance. Once there, his days followed a steady rhythm.

“Each morning I would wake up and immerse myself in a cold creek behind the poet house,” Barnes said. “It became a meditative ritual — sitting in discomfort, connecting with nature, calming my nervous system.”

He spent hours revising and memorizing work. Evenings were communal.

“The artists — writers, painters and other creatives — would gather. We walked together, explored the grounds, shared our art, cried, laughed and built deep bonds quickly. It was transformative.”

More than productivity, the residency gave him space to shed external expectations.

“It meant leaving behind the identity constructs and responsibilities I carry in America — as a nonprofit leader, as a Black man, as someone navigating political and social tension,” Barnes said. “I allowed myself to just be human. No defensiveness. No survival mode. Just grounded, childlike presence.

“That freedom felt healing.”

Being abroad also sharpened his awareness of life back home.

“I feel closer to understanding who I am,” he said. “I also feel more aware of how normalized violence, division, and emotional weight are in American life.”

Artistically, the experience reshaped his priorities.

“In spoken word and slam spaces, there can be pressure to impress,” Barnes said. “Now I’m more focused on painting something visceral and honest.

“I want to share truth, not impress.”

Investing in the next generation

Back in the Midwest, Barnes continues building creative community through Young Lions Roar, a creative empowerment initiative offering workshops, school partnerships, open mics and public events.

“In the Midwest, where arts infrastructure can be limited, we have freedom to experiment,” he said. “We brainstorm, implement, try things, fail and try again.”

His time abroad also expanded how he views interdisciplinary art.

“Being around visual artists influenced how I see poetry interacting with other mediums. That perspective will shape how we serve youth.”

For young writers — especially young Black writers in the Midwest — his advice is direct.

“Write often. Don’t avoid the uncomfortable,” Barnes said. “Share the joy, the grotesque, the beautiful — all of it. And find spaces that support your art.”

After more than two decades of writing, Barnes says the relationship continues to evolve.

“My responsibility is honesty,” he said again. “How that honesty transforms someone is up to them.” Barnes’ most recent book, I Took the Wrong Path, is available here. You can explore more of his work, upcoming performances and initiatives here.

Maxwell Knauer is a staff writer for Watershed Voice.